Last week I moved out of my house in North West London. In 8 years in London I have changed 7 houses, which has made me an expert in moving. I was looking for a Van with a driver (a “man with a van”) to move my stuff in a storage space in South London, about an hour’s drive from my flat. I used a ridesharing platform, which brands itself as “Uber for Vans”. That was what I was actually looking for. I wasn’t confident enough to drive a van across London during rush hour, and I had bad previous experiences with individual van drivers.Once, a guy was 90 minutes late and when I asked to pay a reduced price he kept my stuff in the van and threatened to drive away. Some others come up with the craziest of excuses in a -perhaps understandable- attempt to make some extra money. In one case, I had explicitly explained to the guy that my stuff will completely fill his van, and once we unload he asked for more money because I had too much stuff. I am generally aware of the difficult nature of this job, so my decision to use an Uber-like service was not so much a move against private drivers, but rather an attempt to minimize the number of things could go wrong in a turbulent period of my life. I wanted to agree on a (more or less) fair price, stick to the time schedule, get the job done, and go home (once I find one).

At the same time, I know that rideshare platforms keep a good amount of the fair as service and booking fees (Uber seems to keep more than the advertised 25% in the US) and they pay the drivers a few days later. So my intention was to give the driver a tip anyway, probably as a way to counter-balance the fees charged by the platform and the slight guilt that came by using one.

This became easier as the van driver -let’s call him Mike- arrived 45 minutes earlier than the agreed time. All my stuff were packed, neatly organized, and ready to go, but they were still on the third floor, in the corridor outside my flat – the building had a lift. Mike offered to help me put them in the van for an extra £15. I gave him a bit more than (“God bless you”, he said) that and we started moving the boxes.

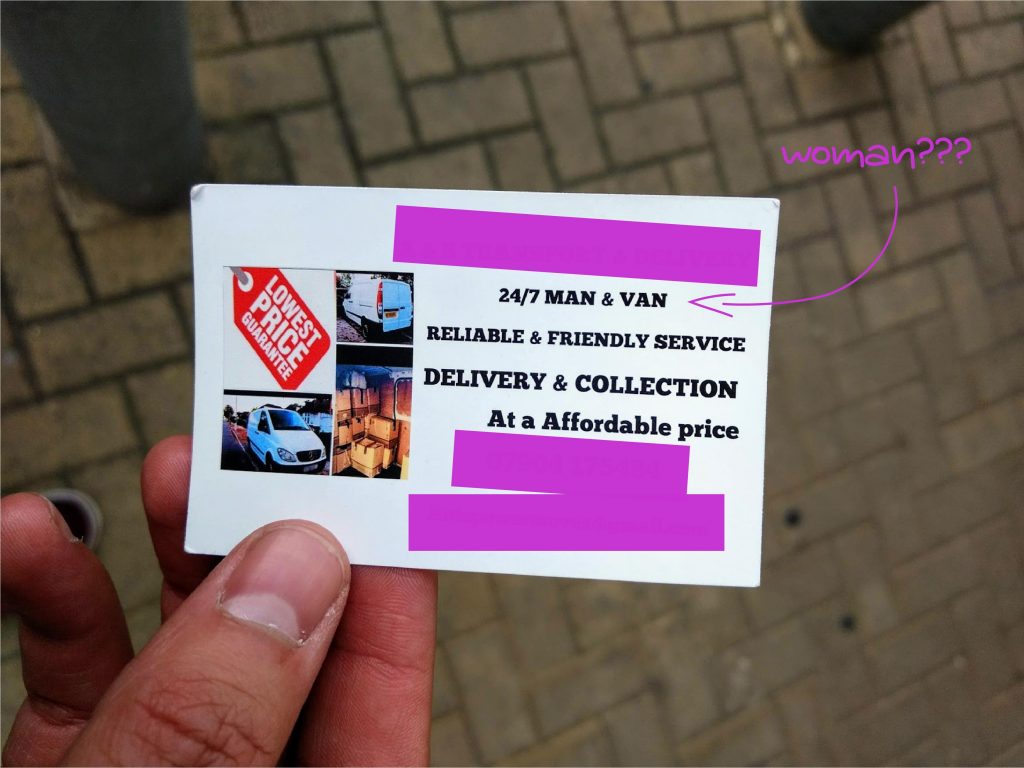

It was then when I noticed that Mike was not alone. A lady -let’s call her Diana- stepped out of the van and started carrying boxes as well. “It is a man and a woman with a van”, I thought.

I immediately assumed that she was there in a casual way, for company, or for offering an extra pair of hands when needed. But once we started heading towards the storage space, I realized that that was not exactly the case. Diana was constantly on her phone (and on Mike’s phone), dealing with job requests, deciding on the optimal route, and advising Mike on which job to accept and which one to reject. Something between a human algorithm and a co-driver in a rally car, she embodied what to me looked like “van economics”. With a bit of deliberate naivety, I asked her if she is a professional co-driver. “She is the technical manager”, Mike responded with a big laugh. “I am on several platforms and is hard to deal with every request (he mentioned Facebook and some others which I didn’t know, I think they were 6 or 7 in total). Diana helps me with that”.

I think I have a broad understanding of how the gig economy works, but I have to admit I didn’t expect to see a “technical manager” on board. As a designer, I am fascinated by the ways people exploit their material world (both physical and digital) to improve their conditions. It is no accident that this happened in a van, because a van, unlike bikes and cabs, can at times afford an extra person. But is exactly this “extraness” that worries me. To see another person –another woman– doing unpaid and unrecognized labour. To see that what I thought as work -and pay- for one person, would actually require -and subsidize- two. This is another case where the digital economy seemingly “solves problems”, but in reality transfers them from the users to working people. To keep up with algorithmically assigned work, workers have to find new ways to organize their labour. Creative as these might be, they are not without consequences. Is not just that the pay will split in two. Some ridesharing platforms are notoriously bad in recognizing their drivers “worker” status, and paying for holiday, sick leave, and minimum wage. But at least registered drivers can organize and claim what they think is right. This is not the case for the people who are invisible.

Mike said that one day he would like to have his own van hiring company, and hire other drivers. I asked if he had thought of working together with other people, instead of managing them. To illustrate what I had in mind, I started sketching out how this might work, and invited the driver and my co-rider to contribute. Roles like Diana’s, no matter how small, can inspire design based on entirely different values. Starting from that, we drafted a list of features, which I completed at home.

>> A platform that would handle job requests would be created. This platform would be worker-owned and controlled.

>> This platform would work as an aggregator, scrapping ridesharing and social media platforms for jobs. Members would be faced with one interface instead of many, something like Booking.com for van drivers.

>> Next to each job, a calculator would calculate the net profit, deducting service and other types of fees, so workers can know how much they can actually earn.

>> A common fund would be created to maintain the platform, and pay for everyday and unexpected costs.

>> Instead of jobs being accepted or rejected, members of this platform would be able to forward jobs to colleagues.

>> Drivers would agree to stick to the maximum working hours, and take frequent breaks, both for their own safety and well being, and to avoid monopolizing the field.

>> In agreement with local authorities, physical spaces would be created, in which drivers could meet and rest.

These are as good as one can make up during a ride. They are a bit simplistic, and ignore some of the mechanics of ridesharing platforms (e.g. an Uber driver needs to accept a minimum number of jobs to stay “active”). I am also sure that, in some form or capacity, similar platforms already exist. But that wasn’t a story about existing ideas that live somewhere else. It was a story that we crafted together, in a van, that saw – and showed – the value and potential of the invisible work taking place there. Was not about novelty or “innovation”, but about enacting reflexivity and opening new ways for relating to our labor, to ourselves and to each other. Is not enough, but it could be a start.

We went on switching between serious and lighter topics. Mike and Diana are of mixed heritage. Mike had origins from Jamaica, Cuba and a couple of other countries of Latin America and Southeast Asia. At a point, they were discussing how mental issues are not discussed within the black community. “Is it because of pride?”, I asked. “Yes. But I am very expressive, I cannot hide”, Mike replied.

A funny moment was when I spotted Mr. Burritto and Mrs. Burrata. “Take a photo, take a photo”, Mike said

We arrived at the storage space on time. Mike helped me unload the boxes, whereas Diana was speaking on the phone. Part of the job, I thought. In the end, we decided to stay connected using the product of an old, but truly radical technology: typography.

Mike’s card