I have been listening to lots of Noods radio (was really happy to come across Greek electronic music pioneer Lena Platonos in one of its lists), reading the Cable, and listening to Bristol history podcasts. In the last one, host Tom Brothwell talked to author and historian Mike Jay about the story of the Pneumatic Institution, a medical facility and research centre in Hotwells, Bristol. Despite being relatively short-lived, it gathered under its roof some of the greatest scientists of the time. The institution was established by physician and scientific writer Thomas Beddoes at 6 Dowry Square in 1799. Its primary purpose was the application of synthetic gases for treating tuberculosis and other lung-related diseases – even though the institution was open about its experimental nature and didn’t brand its services as ‘therapy’. The experiments were primarily conducted by Humphry Davy, a Cornish chemist and engineer who would later become president of the Royal Society. One of the gases Davy tested, nitrous oxide, had some peculiar side effects. The recently synthesized gas would have a ‘curious sweet taste’, and cause feelings of euphoria and analgesia. The scientists set up a ‘salon’ in the basement of the Pneumatic Institution, where poets, actors, and other locals, would gather to test the gas. Davy would later write that nitrous oxide had the potential to be used as an anesthetic in surgery. Despite its potential, nitrous oxide had no effect on treating tuberculosis. The Pneumatic Institution was unable to attract funding, and eventually closed down in 1802. Thomas Beddoes continued to offer his remedies to locals, including many deprived ones, and printed therapies in leaflets, in a form of proto-open science.

To conduct the experiments, new technologies such as inhalators and other medical devices had to be designed. The chief engineer was no other than James Watt, to whom the invention of the steam engine is attributed – even though in reality he redesigned it to make it more efficient and easy to manufacture. Watt’s name became thus synonymous with the Industrial Revolution. Quite literally, that is, since the name of the Scottish inventor has been adopted as the official unit of Power. The industrial revolution, and Watt, as a consequence, will therefore come to signify power, progress, and reason. The story of the Pneumatic institution, however, reveals a more obscure side, one in which the inventor, being a social actor amongst many, experiments with others in often unconventional ways.

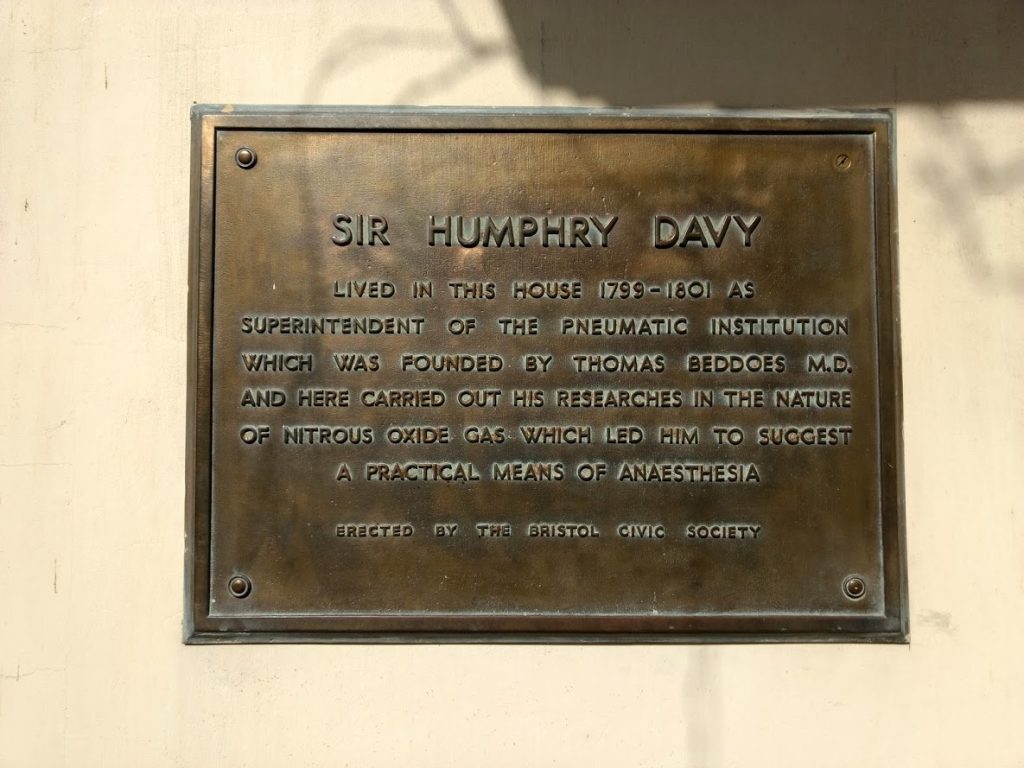

A few weeks ago, I took a walk as a way of clearing my head from writing. I walked from my house down to Dowry Square in an almost psychogeographic way, keeping an eye for traces of the Pneumatic Institute. There is not much on-site, apart from a plate dedicated to Humphry Davy.

On my way back though, I had a happy encounter. A laughing gas canister is no unusual sight in Bristol. Nitrous oxide consumption is popular amongst youngsters and party-goers, and there are recent calls for tightening the legislation around this drug, which is illegal to sell, but legal to use. The use of drugs for recreational purposes is long debated, and is not my point of concern here. I am more interested in the canister as a popular object of a youth culture that exists in a state of failed futures – as a quasi-euphoric, quasi-hauntological object. The sight of empty canisters scattered around the city can equally allude to the generalized melancholy of the present, as well as to the ecstatic atmosphere of the night before, a remnant itself of Britain’s hedonic past.

I started wondering if, by extending the past further backwards, new futures could be imagined. In a sense, the humble canister is but the distant descendant of the techniques and devices developed by Watt and his colleagues a few blocks down the road. I started wondering how the canister can bring together pasts and futures, and people from different professions and backgrounds, including young ones, around issues of science and technology. Is, for example, the work of the pneumatic institution survived in other devices, and have these played a role in fighting Covid-19? And what are the stories, and design’s fictions, that can help construct these publics? I had but questions when I reached my place, and this text highlights process over outcome. But I hope that different stories about science and technology could help us imagine otherwise. Stories in which scientific process and technological innovation is not solely driven by the market, and measured by the yardstick of economic impact, but remains a painstaking and indeterminate human endeavor, both heuristic and euphoric, one of the many meaning-making systems of the world.

The story of the Pneumatic Institution tells how science works in peculiar ways. 50 years after the institution closed its doors, and driven by the progress of surgical operations, nitrous oxide became the most popular anesthetic, and one of the greatest medical applications of the 19th century.